I briefly introduced fuzzing earlier in the series, citing it as the second primitive upon which application testing techniques are built. OWASP has a more in-depth definition available here. We also have a video on fuzzing with Burp Suite here.

Fuzzing in ZAP

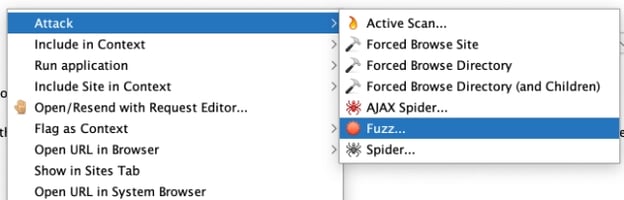

Much like tampering, you can start by locating the request we want to fuzz in the History tab, and right-click it to bring up the context menu.

From there, go into the Attack submenu and select Fuzz…

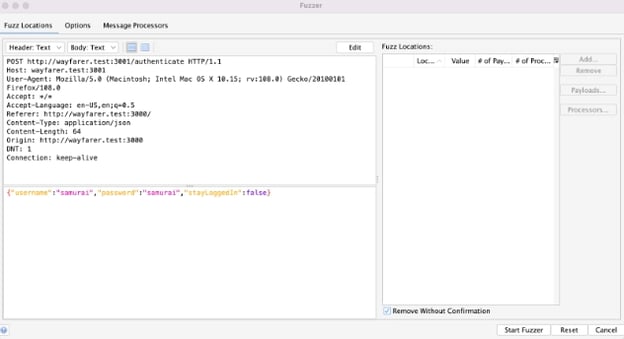

This will open up a dialog showing the request, but unlike the Request Editor, this has an empty list on the right side indicating Fuzz Locations.

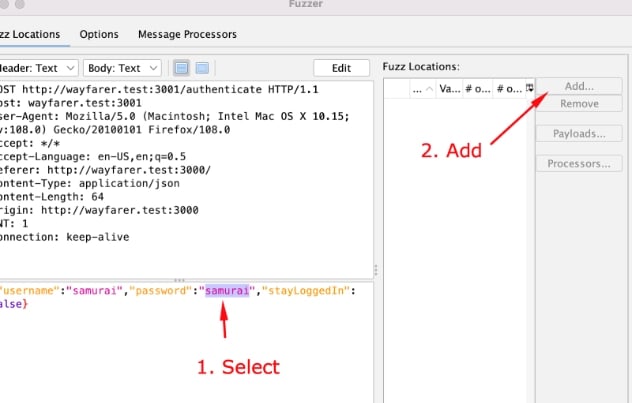

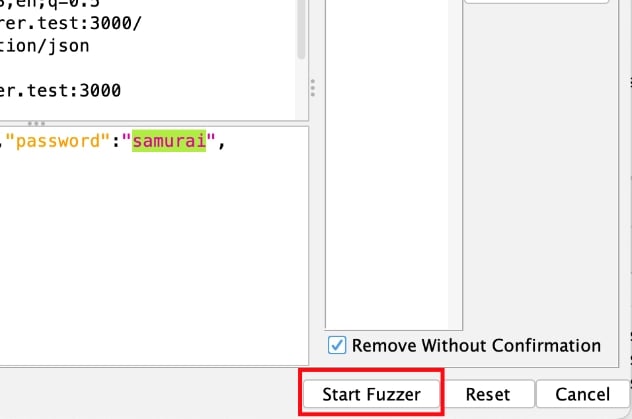

My example request is an authentication payload with a username and password. I could select multiple fuzzing locations, but let’s limit it to just the password field for now. I can select the text, the word samurai in my example, and use the Add… button to the right of the Fuzz Locations list.

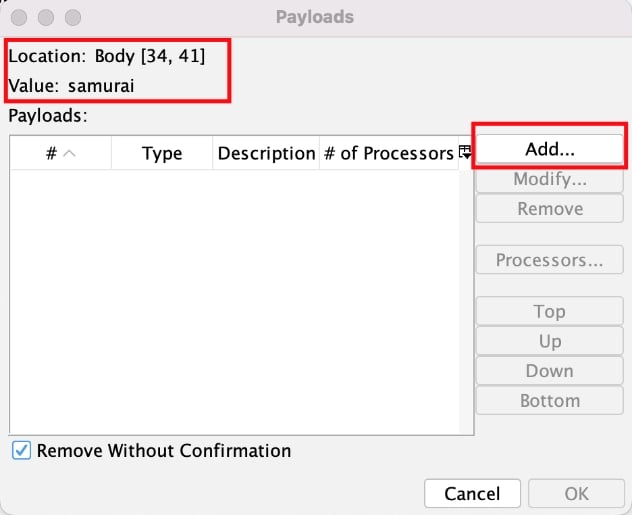

This will open the Payloads dialog, which indicates the location and current value, and has an Add… button.

I’ll click Add…, which will open up yet another dialog to a payload.

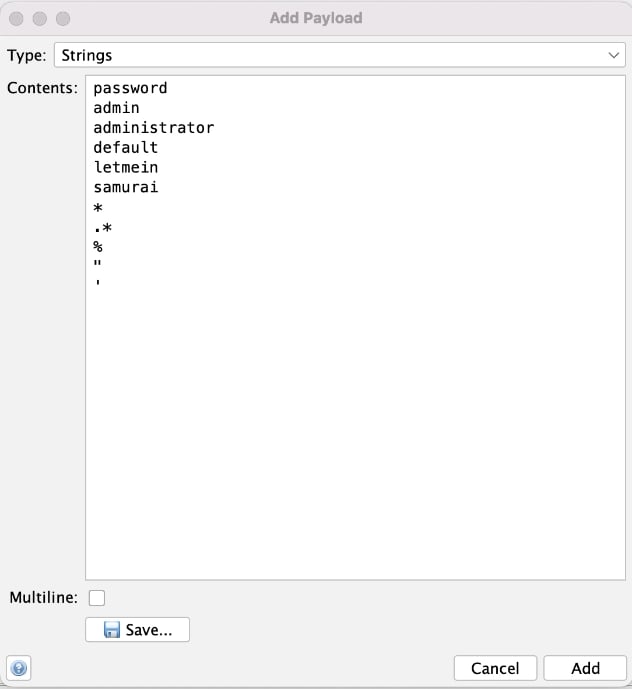

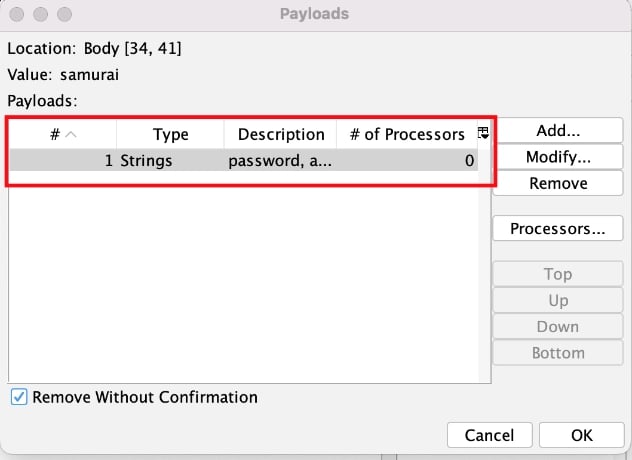

There are many types of payloads, for example it’s not uncommon that I want it to iterate over a range of numbers. But in this case, I’ve left it as Strings and pasted in a list of values just to demonstrate it. I then clicked the Add button at the bottom of this dialog to finish adding my list of strings as a payload. This is now reflected in the Payloads dialog, as shown in the following image.

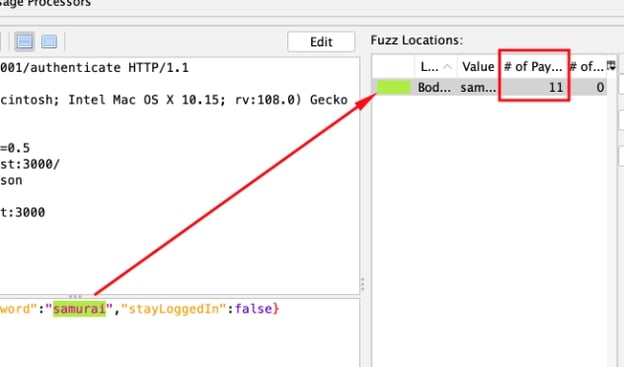

And if I click OK on the payloads dialog, I’ll see the Fuzz Location’s highlighting is matched to selection in the request body. I also have a count in the # of Payloads column of 11, which matches the number of strings I supplied.

Finally, I can click the Start Fuzzer dialog to run the fuzzing operation.

With the default settings for only 11 requests, this appeared instantaneous for me, and populated a Fuzzer tab in the bottom pane of ZAP’s main window, as pictured.

I rearranged my columns into an order that made more sense. The top request (Task ID 0) being the original valid login. Task ID 6 with the payload of samurai was the valid password I threw into the list, and you can see it has the 200 status code and the same size request and response as the original. The majority of the others led to a 401 Unauthorized response, all with the same sizes as each other. If I select one of these, it will open in the Response pane.

It’s exactly what you might expect from an invalid login. Referring back to the list of them, the one interesting response was Task ID 10, which returned a 400 Bad Request, had a payload of a double-quote character (“), and was the only one with an entry in the State column indicating it was Reflected. In other cases this could be an indicator of something interesting. However, in my case, it’s far more benign than that. If I switch to the Request tab, it’s pretty obvious. Because I put that quote character into a JSON structure without escaping it, I’ve malformed the JSON structure, as shown.

If I switch back to the Response tab, you can see that the response was HTML formatted, and just happened to use the same quote characters, so ZAP misinterpreted it as Reflected.

With other payloads this certainly might be interesting, like if I was fuzzing for cross-site scripting flaws. But in this case, it’s a false positive.

Applying this to XSS

Let’s look at a simple example of a classic reflected input. The example request below submits a username and password.

When the response comes back, I can see the username is still populated.

Something that makes this even more significant, is that this isn’t a case where an API call is made and 401 response makes the client show an error message. This response contains an actual HTML fragment containing that value.

Because of the context of this input, my goal as an attacker is to somehow escape the context of the value attribute, normally by closing the quotes. Another option that might work if I can get multiple inputs to reflect would be escaping the existing closing quote. In either case, let’s say I want to fuzz this to check how it behaves with a bunch of different values. So I’ll send this login request to the Fuzzer tool, just like before. I’ve manually written out a nice short-list of payloads to try. Normally I would use something like one of the lists in SecLists, but in this case I’ll keep it very simple.

After I run the Fuzzer, I can see that only one of these was marked as reflected, but they’re all 200 OK. In a JSON payload, I might think that my trailing backslash has escaped the closing quote, and might result in something to pursue. In HTML, it doesn’t fulfill that function, so it has not effect.

I would also like to determine why specifically my double-quotes didn’t break context, so I’ll look at one of those first, and find that quotes are being HTML entity encoded.

For comparison, I’ll run a few payloads against a wide-open unsafe reflection in a different demo app. This time, the input reflection is into a different context. It’s a text node within a div tag.

So my payloads will look to create HTML elements. Now, if ZAP sees my payloads as reflected, there’s almost certainly a cross-site scripting flaw here. Some filtering libraries like DomPurify will remove malicious attributes without fully removing HTML, so my benign <h1>Test</h1> payload could reflect and not indicate a vulnerability. But the only way to know is to try it.

As you can see below, all of them were reflected. And if I take, for example, the last payload (the img tag) and submit it through the browser, let’s see what happens.

As you can see, the pop-up popped up, proving that script execution was obtained.

What about SQL injection or command injection?

The same principle applies to server-side injection flaws, but we don’t generally have the same visibility into how our input is being treated. Still, consider the following fuzz result, also against a login form:

I can see that every entry responded the same way except one. That one in question produced a 500 server error (this is usually not a gracefully handled error). It’s different from the other payloads in that it includes a single-quote (‘) which is how strings are wrapped in common SQL dialects. It also has a space in it, and the others don’t. And if I look at the actual response, I’ll see a stack trace related to a SQL query.

This is where an intentionally vulnerable learning app (OWASP Juice Shop in this case) is different from most production systems. A SQL error could be returned, but often it will be a generic 500 error, and we’d have to do additional detective work to either demonstrate an actual exploit or at least establish better evidence that it’s a real flaw.

In Summary…

Fuzzing is a great discovery technique, but there’s also plenty more that can be done with the tool, including using multiple locations, multiple payload sets, and extra payload processing rules for stuff like encoding.

Take a look at day 5, looking at using Scope and Contexts within ZAP to make it easier to see what you’re doing and keep your attacks on target.